(British Museum, 2 May-28 July 2024)

So, if anyone has been wondering why I’ve dropped off the radar for the past two years, this is the reason… I’m very excited to be able to share this with you at last, and it’ll probably be the first of several posts as we lead up to the opening on 2 May.

Late in 1534, Michelangelo Buonarroti said goodbye to his native city of Florence for what would be the final time. He was 59 years old. Leaving behind his family – his brothers, and his nephew and heir Leonardo Buonarroti – he headed south to Rome, to pick up the threads of his life there, and to turn his attention to one of the most challenging commissions he’d had to date: The Last Judgment, in the Sistine Chapel. By the standards of the age, he was old, and he could reasonably have expected The Last Judgment to form a kind of swansong to a glittering career.

However, it turned out to be merely the beginning of a new chapter, which would last for a further thirty years. And, in that time, he’d be busier than ever before. The story of Michelangelo’s last decades – as he juggled papal demands with the challenges of physical ill-health, bereavement, and spiritual disquiet – form the subject of a British Museum exhibition (2 May-28 July 2024). And they’ll emphasise, I hope, the deeply relatable humanity of a figure regarded, even by his own contemporaries, as ‘divine’.

I’ve put together a short blog post for the Museum, giving an overview of the themes and narratives of the show, so I don’t want to simply repeat myself here. Head on over and take a look at that for a sneak peek, and to orient yourself with what the exhibition aims to do. There will be further official blog posts and videos, both from me and from other colleagues in the Museum, as we go forward, discussing other aspects of the exhibition. I don’t want to steal any of my colleagues’ thunder by talking about their topics, so I’ll do a more focused post on some of the objects closer to the opening date. What I’d like to do here, instead, is to take a more personal path and to talk about how my view of Michelangelo has changed, during the four years I’ve spent in his company.

When I started working on this project, fresh from dealing with Piranesi and, a little while before that, the irascible Mantegna, I was afraid that Michelangelo would simply make up a hattrick of grumpy Italian artists. But my view has changed. I’d still argue that Michelangelo wouldn’t be the ideal dinner-party guest. You’d want Leonardo da Vinci or Raphael at your table instead, charming fellow guests with their effortless charisma and courtly manners. Michelangelo would be harder to draw out, and liable to take offence. But a one-on-one – a lazy chat over a flask of Trebbiano and some fried artichokes in a Roman bar, for example – might be a different matter. As soon as you scratch the surface, Michelangelo becomes vividly, appealingly real – snobbish, articulate, short-tempered, passionate, thoughtful, frugal, wistful, and warm.

What did I know of Michelangelo, before? I knew his work: the muscular power of his drawings; the way he can contort the human body into impossible positions and make us believe it; the bright colours of his frescoes; the tactile elegance of his finished sculptures, and the gut-wrenching poignancy of those unfinished statues, forever struggling to free themselves from the stone. I knew a few of his poems. But I had little real sense of the man himself. I knew what we’re told by Vasari and Condivi (Michelangelo’s assistant and ‘approved’ biographer): the gruff, no-nonsense fellow who wore his boots until he had to peel off his skin along with them; the man who jousted with the irascible Pope Julius II. But now, having read his letters and his poems, and having revisited his drawings and designs, I’ve gained a far richer sense of him.

He could be impossible – short-tempered, often lashing out with no reason – easily offended, even by those he loved most deeply. He bristled at any suggestion that he was an artisan, rather than a gentleman of good family: when his nephew Leonardo sent him a gift of a brass ruler, he wrote back in high dudgeon, accusing Leonardo of treating him like a ‘carpenter’: ‘I was ashamed to have it in the house and gave it away’. Indeed, poor Leonardo suffered the brunt of his uncle’s temper. He received letters complaining about gifts he’d sent, criticising his handwriting (‘I threw it in the fire‘, Michelangelo wrote of one letter, in which Leonardo’s illegible script had defeated him), and offering increasingly blunt and fractious advice on what Leonardo should look for when choosing a wife. But, as with so often, much of Michelangelo’s brusqueness was a front. He cared deeply about the future of his family: he lived simply in Rome so that he could send large sums of money back to Florence, to help his brothers and Leonardo invest in property, and increase the family’s landholdings. His sharpness derived from the constant suspicion that they took him for granted and only really cared for his money.

An element of that came into play, incidentally, shortly after Michelangelo finished The Last Judgment in 1541. He’d been working on it for seven years. It was received with wonder by the Pope and it prompted a blend of awe-struck admiration and controversy for its innovative details – the beardless Christ; the extensive nudity of the saints; the addition of the very pagan figures of Minos and Charon at lower right in Hell. When Leonardo expressed an interest in coming to Rome, Michelangelo eagerly sent him money, evidently hoping to have the chance to show his ‘great task’ to his heir. But, on receipt of the money, Leonardo changed his mind. He invested the funds in his business instead. Normally, Michelangelo would have approved this prudent use of cash. But, this time, he felt let-down. Once again, it looked as though his family were only really interested in what they could get from him financially.

So perhaps it doesn’t come as too much of a surprise to learn that this sensitive, awkward man was also capable of great love and loyalty. He regarded his long-time servant, Urbino, with almost paternal fondness, and was inconsolable when he died young. He spent considerable time musing over the right gift to buy as a wedding present for Cassandra, the woman Leonardo eventually married. His friends were hugely loyal to him in return. The aristocratic poet and reformer Vittoria Colonna wrote him exuberant letters, which show the intellectual delight she took in exploring the religious designs he created for her. His close friend Luigi del Riccio was the recipient of fond and teasing notes, along with a series of epitaphs written on the premature death of Luigi’s young kinsman Cecchino Bracci. The Portuguese artist Francisco de Holanda, who knew Michelangelo in Rome in the late 1530s, wrote a series of dialogues in which he appears as taciturn, thoughtful and courteous – impatient with frivolity and devoted to the merits of hard work.

And what could be more affecting than to see this prickly middle-aged man fall in love – perhaps unrequited; certainly (in my view) platonic – with the beautiful young nobleman Tommaso de’ Cavalieri? Tommaso prompted the creation of exquisite gifts: ardent love poems and refined drawings of episodes from the Greek myths (like the Phaeton shown at the top of this post), which offered moral guidance from an older and more experienced admirer. Michelangelo also wrote him letters which, to modern ears, are rapturously romantic (though, as with Shakespeare’s sonnets, we should remember that the mores of the time were rather different). In 1533, a year or so after he’d met Tommaso on a brief visit to Rome, and a year before he moved back permanently to the Eternal City, Michelangelo wrote from Florence, to reassure the young man that he hadn’t forgotten him: ‘I could as soon forget your name as forget the food on which I live,’ he wrote. ‘I am insensible to sorrow or fear of death, while my memory of you endures.’ Which of us wouldn’t dream of receiving a letter like that?

A quick note: why did we want to focus on ‘the last decades’? Well, the idea of the artist’s ‘late period’ is something that has always sparked interest and there hasn’t been a focused show of this kind in the UK. My colleague Hugo Chapman did a brilliant show covering Michelangelo’s whole career back in 2006, but that focused on drawings from only two collections – the British Museum itself, and the Teylers Museum in Haarlem. Carmen Bambach did a real magnum opus of an exhibition in New York in 2017-18, which covered everything, and in which I spent eight very happy hours: something on that scale is unlikely ever to happen again. And, in Milan, they did an exhibition focused on their glorious Rondanini Pietà, which homed in on Michelangelo’s last ten years. But we’re looking at the entirety of the last Roman period, and really trying to focus in on Michelangelo the man, bringing together letters and poems alongside his drawings, to look at how he faced the challenges of growing old while still being so in demand.

In recent years, we’ve fortunately moved well away from the idea that, in old age, work is somehow compromised or diluted. The emphasis is now on the richness of accumulated experience. Artists like David Hockney, Maggi Hambling and Bridget Riley continue to produce insightful, inventive and challenging work well past pensionable age. Picasso’s imagination remained fertile and gloriously randy right up until the end. Mary Delaney didn’t even start creating her beautiful botanical decoupages until she was in her seventies. Titian’s late style is an almost impressionistic palette of golds and reds and blacks, where the contours dissolve into a shimmering Venetian haze. And Hokusai, who reinvented himself at each stage of his life, wrote:

of all I drew by my seventieth year there is nothing worth taking into account… by one hundred I shall perhaps truly have reached the level of the marvellous and divine. When I am one hundred and ten, each dot, each line will possess a life of its own.

cited by Gian Carlo Calza in his introductory essay to Hokusi (Phaidon: 2004), p. 7

Michelangelo might not have sympathised completely with Hokusai’s renunciation of his younger self, but he did share the Japanese master’s irrepressible work ethic. He died shortly before his 89th birthday, on 18 February 1564, and was working right up until the end: the most ambitious project of his career, the rebuilding of St Peter’s Basilica in Rome, was still underway at the time of his death. Only six days earlier, he’d spent the whole day on his feet, chiselling away at his marble sculpture of the Rondanini Pietà, a poignant vision of grief in which the Virgin Mary supports the slumped body of the dead Christ. By this point his hands were too unsteady to hold a pen – he’d dictated his letters to others since the previous December – but he was determined to carry on, unable to simply sit down and wait for the end. Indeed, on 14 February, only four days before he died, a friend found him wandering around in the rain outside his house, having decided that he was going to go riding. Michelangelo was not going to ‘go gentle into that good night’.

And yet, for him, that night was ‘good’. Devoutly Catholic, Michelangelo had no doubt that his soul was in God’s hands. He’d been religious since his youth, when he’d been impressed by the charismatic preaching of Girolamo Savonarola in Florence, and in later life he was constantly aware, like a niggle at the back of his mind, about the need to purify and prepare his soul for death. He sent large sums of money back to his family in Florence and sought out opportunities for charity; from the 1540s onwards, his poetry increasingly focuses in on his desire for redemption. And yet, like everyone else at this date, he found himself in a time of turbulent change. The Reformation in Northern Europe, and the desire for reform within the Church, added new uncertainties to faith. What did you really have to do to get to heaven? What was necessary and what was just additional glitter and glamour added by the Church? How could you be sure that you were living a good life, and hadn’t accidentally fallen into error?

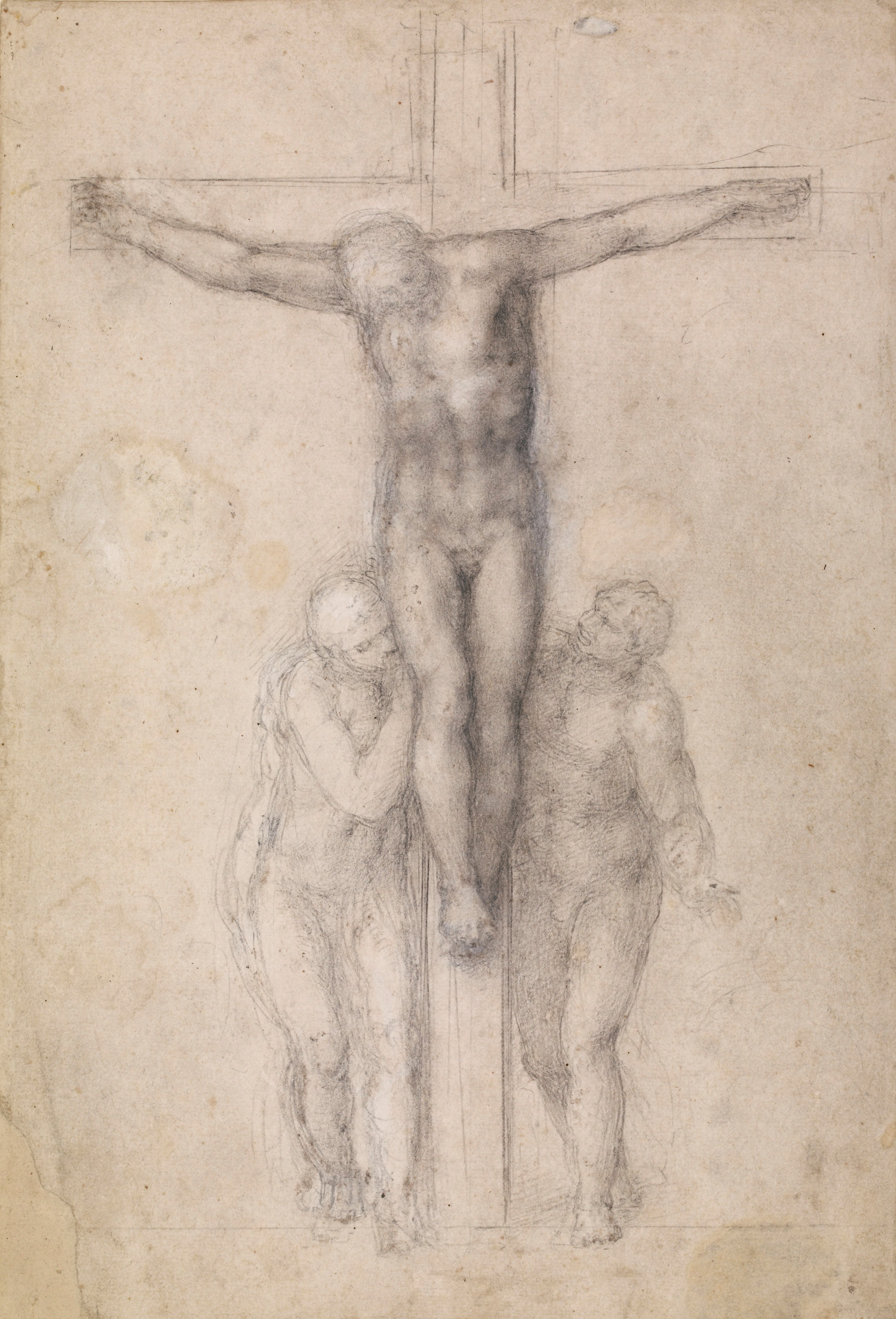

Michelangelo’s spirituality was a very personal and private thing. He doesn’t go into detail in his letters about what he actually believed, although we know that he put great store in the sacraments. The meditative quality of his faith was probably influenced by the example of Vittoria Colonna, whose sonnets addressed Christ with visceral intimacy and who was a key member of the spirituali, a group of evangelical Catholic reformers. Vittoria used her writing and poetry as a way to meditate on key scenes from the Passion – on the Deposition; the Lamentation; and, above all, the Crucifixion, that moment at which Christ sacrificed himself to redeem humanity. Michelangelo designed a Christ on the Cross for her, as seen in a stunning drawing in the British Museum, where Christ is a forceful, living figure, tormented by his pain and yet triumphant. As he grew older, Michelangelo found himself returning more and more often to Crucifixion imagery, which offered so powerful a combination of pathos and physicality.

In the last ten years of his life, Michelangelo produced a series of drawings of the Crucifixion. They don’t seem to have been deliberately conceived as a set, and can’t be connected with any known commission. They revisit the theme almost obsessively, each time showing signs of reworking and rethinking. In one, the Virgin Mary, at the side of the cross, has her arms folded over her chest in acceptance of God’s will. In another, she clings to the upright of the Cross, pressing her face against Christ’s body. Sometimes Christ’s face has been reworked, so that we can no longer tell whether he’s meant to be looking down at his mother, or his beloved disciple St John the Evangelist. Sometimes the mourners disappear completely: in a couple of the drawings, Michelangelo hones in on Christ alone, the wracked and ravaged body on the Cross, through whose blood he believed he would be saved. For me, these drawings are spiritual meditations, ways for Michelangelo to process his emotions about sacrifice, mortality and salvation. They’re visual parallels to the poems in which Michelangelo stresses his desire to strip away the distractions of the mortal world:

My innumerable thoughts, all full of error,

ought to be, in the last years of my life,

reduced to a single one, which then may act

as a guide towards its serene, eternal daysTranslation by James Saslow

Since the very beginning, I’ve wanted these drawings to form the closing section of the exhibition (except for a brief look at Michelangelo’s legacy, as you leave). My hope is that the show offers people a chance to get to know Michelangelo more as a person, whose life and work was shaped by the dynamic and challenging times in which he lived. You’ll have passed through sections which look at his large-scale public works – The Last Judgment, or his architectural designs – and sections looking more closely at the gifts he gave to his friends, or the religious context, or his collaborations with Marcello Venusti.

And yet now, at the end, you should feel that you’re alone with Michelangelo, looking over his shoulder as he faces that last boundary that all of us, sooner or later, have to cross. Sometimes you can see the quivering line of his chalk – which, pace my colleagues who disagree, I think probably is a sign of his failing dexterity. He doesn’t draw straight lines freehand any more: he turns to rulers, which give a strong, hard line often at odds with the fugitive grace of the figures. In his glorious late poem Giunto è già ‘l corso della vita mia, he regrets the way he has allowed the pursuit of worldly fame and renown to blind him to more important considerations:

Neither painting nor sculpture will be able any longer

to calm my soul, now turned towards that divine love

that opened his arms on the cross to take us inTranslation by James Saslow

I think that anyone who spends an extended time with Michelangelo conceives their own idea of him. His letters and biographies certainly give us enough material for a myriad of interpretations, and perhaps the Michelangelo we end up with says more about us than it does about him. The Michelangelo I’ve ended up with is, perhaps, a rough diamond, his abrasive surface hiding a vulnerability that rarely comes to light – but, when it does, it’s startling. We can look at these drawings – which have somehow, miraculously, survived half a millennium – and we see things which resonate with something deeply human within ourselves. In his last thirty years, Michelangelo is constantly weighing up the physical and the intangible; the mortal and the divine; the earth-bound and the sacred. His familiar muscle-bound bodies become more compact, more solidly anchored to the earth, like the weighty saints of Giotto and Masaccio he’d seen as a young man. And yet, even here, there are exceptions: the occasional Christ, or the young Virgin holding her baby in her arms, where the figure becomes attenuated, gracefully indistinct, the contours dancing tantalisingly out of reach.

Michelangelo spoke of turning his back on art in order to devote himself more fully to the contemplation of eternity. Perhaps we’re fortunate that, instead, he used the former in the service of the latter, creating a deeply personal and poignant body of work that continues to captivate even to the end.

I’m so excited that I’ll be in London this summer and can see this exhibit! Now to read a good biography of him in preparation. Congratulations on the show!

Thanks so much! At the risk of horrendous self-publicity (if this post isn’t already guilty of that), there will be an exhibition book, which is already available for pre-order on Amazon (though not yet on the British Museum online shop), but of course that only covers the last thirty years. For a good, readable biography covering all aspects of Michelangelo’s life and career, I’d recommend William Wallace, Michelangelo: The Artist, the Man and his Times, which I really enjoyed and which I think is one of the best introductions to Michelangelo – it really gives a sense of him as a person.

Terrific, thanks so much!

You’re very welcome 🙂

This sounds fascinating. I wish I was coming to London this year and could see it but it doesn’t look like I’ll be there. Now that I’m retired I considered going to the Dorothy Dunnett meetings in Edinburgh this year for the first time and stopping through London, but I think that will need to wait at least a year.