★★★★

(Teatro Pergolesi, Jesi, 2011)

There’s no middle ground for rulers in Baroque operas. They’re either tyrants demanding submission at any cost, or weak figures who are manipulated by their ambitious courtiers. Alessandro, otherwise known as the emperor Alexander Severus (208-235), is one of the latter. When this opera opens, he’s very much in love with his new wife Salustia, the daughter of his general Marziano, and doesn’t understand why his mother Giulia dislikes her so much. Salustia, however, knows the reason only too well.

Giulia is used to being the leading lady of the court and can’t countenance anyone taking that away from her. Allowing her resentment to blossom into hatred, this jealous dowager uses her influence over her weakling son to trick him into renouncing Salustia. This proves an unwise move. Salustia’s father, the proud Marziano, has been itching for a greater taste of power. His daughter’s banishment convinces him it’s time to act. And so the question is not only whether Salustia and Alessandro will be reunited, but also whether anyone will discover Marziano’s plot before it’s too late.

Salustia was Pergolesi’s first opera and you get the feeling that he was keen to show what he could do. Fortunately he had plenty of opportunity for drama. The opera’s libretto, adapted from Apostolo Zeno’s original, was crammed with virtually every possible plot device. There were conniving generals; poisoned chalices; women dressed as men; and thwarted love; not to mention a berserk mother-in-law and a finale in which one character is literally thrown to the lions in the arena. Pergolesi obligingly gave each character at least one very good aria. Those that stay in my mind are Alessandro’s virtuosic A un lampo di timore in Act I and Salustia’s splendidly feisty Tu m’insulti? Io non pavento in Act 2. But all the composer’s hard work was thrown into jeopardy at the final hurdle. Shortly before opening night, his primo uomo – the castrato Nicolo Grimaldi, playing Marziano – dropped dead. It was too late to find anyone else of comparable status so, thinking quickly, Pergolesi rewrote the role of Marziano. He changed its register from alto to tenor and promoted Francesco Tolve, who’d been hired to sing the minor role of Claudio (he’d also been the original Artabano in Vinci’s Artaserse two years earlier). To replace Tolve, Pergolesi drafted in the young castrato Nicolo Gizzi and transposed Claudio’s role from tenor to soprano. Getting a Baroque opera on stage often seems to have been a fractious business, but this must take the biscuit for last-minute crises.

The set of Salustia recalls the Colosseum with its ranked arches

This 2011 production at Jesi follows the revised setting, with Marziano as a tenor. (The modern premiere of the opera, in Montpellier in 2008, kept Pergolesi’s original music and had him as an alto.) I liked the quirky 18th-century-style costumes and the sparse setting, which was dominated by the arched facade of Alessandro’s palace. The windows were often used to frame characters: I was reminded of the similar aesthetic of Sant’ Alessio.

Although I recognised some of the cast’s names, I hadn’t heard any of them sing before. They were all impressive, to the point that it seems slightly unfair to pick favourites. Laura Polverelli makes a great Giulia, playing the role with such maniacal relish that it’s clear bunny-boiling is only a short step away. Her aria Or che dal regio trono has one of the catchiest motifs in the entire opera. As the secondary lovers Albina and Claudio respectively, Giacinta Nicotra and Maria Hinojosa Montenegro were very strong: I thought Nicotra’s voice in particular was beautifully rich. And the Romanian countertenor Florin Cezar Ouatu impressed me as the hopeless Alessandro: his high-set voice, with its shimmering tremolo, works perfectly for the character. He seems on the verge of cowering throughout, and there’s one brilliant moment when he sings an aria holding a (real) hen, for no apparent reason; one wonders what the hen made of it all. I couldn’t help thinking that Alessandro, who responds to any crisis by whimpering about how terrible it is for him, would make a great pen-friend for Artaserse.

It’s only since watching the opera that I’ve realised Ouatu is the same Cezar who sang for Romania in the Eurovision Song Contest in 2013. Wow. I’m very glad I only discovered that afterwards. It would have slightly spoiled things. Of course, I’ve now spoiled it for all of you. No, really, go and take a look. Who says that Baroque artists are niche?

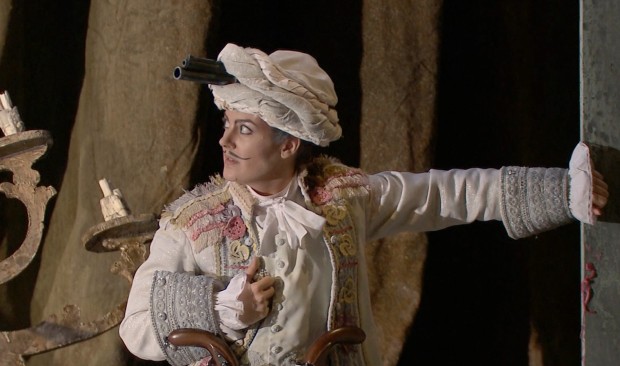

Alessandro (Florin Cezar Ouatu) and Giulia (Laura Polverelli)

Let’s pick up our jaws from the floor and move on. The real highlights, as it should be, are Salustia and Marziano. As the former, Serena Malfi spends much of the opera suffering elegantly: her voluptuous voice is gorgeous on the slower arias. However, she also pulls out all the panache for Tu m’insulti, which offers a hint of a fierce, defiant Salustia who – had the librettist allowed her more stage time – might have made the opera even more fun to watch. Crucially, she also has a convincing chemistry with her Alessandro, whom she seems to love deeply despite him having less backbone than an eel.

But, for various reasons, the palm is carried off by Vittorio Prato’s Marziano. It’s partly that he gets the best music, which was originally intended for Grimaldi, and Prato’s resonant baritone swashbuckles its way through his transposed arias with ease. He’s not quite the grizzled general the plot requires: it’s slightly ridiculous that he’s meant to be Malfi’s father, although someone’s tried to put some grey powder in his hair as a concession. But he gives a wonderful performance. From his first entrance, Prato swaggers: he’s easy on the eye, looks rather dashing in frock coat and breeches, and knows it. The character knows it too: Marziano is ultimately less concerned about his daughter than he is about his own honour, and the only person who really matters to him (apart from himself) is Giulia. This production gives an erotic tinge to the interaction between these two: even though Marziano hates Giulia, he’s attracted by her power. Ultimately the opera comes down to their struggle for supremacy, while around them the four young lovers move like satellites caught up in the gravity of their elders’ machinations.

It’s certainly not the most familiar of Pergolesi’s operas, but it’s a little gem. The story becomes a little daft at times – it really does feel as if the librettist has pulled out all the most dramatic events from the collected works of Metastasio and shoved them into a single opera – but it’s fun and that’s what matters. And it’s rather fabulous to see the young Pergolesi at work: only 21, but already brimming over with ideas and confidence. Bravo to the team at Jesi for bringing Salustia back to life on film and introducing me to such an exciting group of singers. I’m looking forward to exploring more of the Jesi DVDs.

I feel obliged to add a word on the history. Salustia is loosely based on fact which has been creatively shoehorned into an operatic formula. Sallustia Orbiana was the beautiful but unfortunate first wife of Alexander Severus. Her father (called Sallustius, not Marziano) was a senator rather than a general, and was judged to have committed treason when he appealed to the Praetorians to protect his daughter from the queen mother’s intrigues. In real life, Sallustius was executed and Sallustia ended her days an exile in Libya. Whether or not this reflects what happens in the opera, I’ll leave it to you to find out…

The belligerent Claudio (Maria Hinojosa Montenegro)

Screen captures in this post taken from here

Ouatu's Eurovision participation was a bit of an odd thing but that tells you something about Romania's particular quirks. Singing is still more of a democratic affair than in Western Europe – classically trained singers (even those with established operatic careers) habitually sing traditional stuff and even pop songs in public. Far as I know he's sung quite a bit (the usual roles) in Italy.

I've yet to hear Malfi live but she's already sung in Il Barbiere at ROH so she seems to have arrived.

Well, if Romania have a habit of putting forward native classically-trained countertenors for their Eurovision entries, let's just say I've got high hopes for this year… Valer's not doing anything else in May, is he?

You're right in that Ouatu has continued doing classical stuff but he seems to have got onto the slightly more pop classical circuit, at least in the immediate aftermath of Eurovision, when he did quite a few concerts with Andrea Bocelli. I'd really like to see him do another Baroque role, though. He's got an interesting voice and he's really not bad at all. I'd like to see if he can do something a bit more forceful. As for Malfi, I think she's singing in Figaro at Glyndebourne this summer; HM and I reckon she must be the Countess. She really impressed me.

Hm, I wonder if, after having grown up in Germany Valer has quite the same relationship with Romania. Or if he cares about Eurovision at all 😉

Malfi, as mezzo, will sing Cherubino. Mezzos could, at a push, sing Susanna but not Contessa. I just noticed Gyula Orendt (Orfeo) is the Count, quite intriguing.