(National Gallery, London, closed on 29 July 2018)

And I’m late again in posting about an exhibition. Sorry about this: summer travelling really isn’t conducive to getting things done on time. Anyway, it’ll be a good way to look back on a lovely show. Now, I’ll be upfront: I have not traditionally been a great fan of Monet. I don’t dislike his pictures – he doesn’t make me shudder, as some late female nudes by Renoir do – but, when I’ve seen his paintings in museums, they’ve rarely moved me to anything more than dutiful appreciation. As ever, much of my indifference was due to a lack of understanding. And that’s why the National Gallery’s present exhibition was such a revelation to me, because it rescued those waterlilies and seascapes and rivers from their chocolate-box ubiquity and reframed them as part of a dynamic story of experimentation and evocation. Monet was a painter of light and air and water, but he was also an inveterate painter of architecture, and this exhibition shows how he used a variety of man-made structures to order his compositions, emphasise the interplay between man and nature, and display the transformative power of light.

Monet’s early works don’t show much of his later genius. Raised in Normandy, he was trained in the traditions of the old masters, and his earliest works show a clumsy synthesis of the picturesque and the realist. The houses in The Lieutenance at Honfleur (Private Collection), painted in 1864 when he was 24, are made up of thick, flat blocks of colour, as if he’s struggling to articulate what he sees. The same is true even of the later Windmills near Zaandam of 1871 (Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam), as if the exotic shapes have left him struggling to bring the scene together. But by this later point he’d already grasped the importance of light: in his Street in Sainte-Adresse of 1867 (Clark Art Institute, Williamstown), he’d introduced a thin line of sunlight at the end of a receding lane, suggesting spatial depth and hinting that, if only one could turn the corner at the end of that lane, one would come out into an open and dazzling place.

Claude Monet, The Church at Vetheuil, Southampton City Art Gallery

For me, Monet’s magic is at its most powerful when mixed with water. It was in his Hut at Sainte-Adresse (Musées d’art et d’histoire, Geneva), also painted in 1867, that I saw the beginnings of his familiar style. Here a ripple of light breaks down the leaves and the sea into terse brushstrokes of blue, green, ochre and white. Water was becoming his metier and he experimented further in Houses on the Banks of the Zaan, Zaandam of 1871 (Städel Museum, Frankfurt). The river gives back a shimmering reflection of the houses’ candied colours, while the elaborate curlicues of their gables have been laid in with thick swirls of white impasto. For me, though, the apogee of these early pictures was The Church at Vétheuil, painted in 1879 (Southampton City Art Gallery), in which the watery reflections are broken up into thick dabs of pinks, greys and whites and you sense the brilliant sunshine bouncing off the white walls of the houses and the yellow stone of the church. Monet paints thinly and daringly in parts: if you look closely at the sky, what you first see as clouds turn out to be patches of bare canvas peeping through the blue.

In the following decade, Monet continued to experiment with views in Normandy and, if we’re to keep to the exhibition theme, this section showed him overwhelmed by the architecture of nature. His style maintained its experimental quality, but even in the 1880s you can see him nodding back to the masters of the sublime. In The Church at Varengeville of 1882 (Barber Institute, Birmingham), he chooses a view of a type that would have appealed to an English watercolourist of eighty years earlier, yet he makes changes to its impact. The two trees, rather than serving as a neat framing device (itself a custom borrowed from Claude Lorrain), proudly interrupt the sweep of the land; and nature is drenched in the fierce colours of sunset. Here are the fiery reds and oranges of the foreground heather; further back are the sweeping greens, blue and reds of the slope up towards the headland, which seems almost to be melting: land on the brink of becoming water.

Claude Monet, View of Varengeville, John and Toni Bloomberg Collection

Monet was constantly bewitched by the theme of cliffs against the sea, seen from above or below: that same headland at Varengeville appears twice more in this room: once in a tamer daytime view (Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio), but most dazzlingly, for me, in the variation titled Morning Effect (Collection of John and Toni Bloomberg). Here we see the little chapel from beneath and the picture is dominated by the cliff itself: a symphony of stone in pinks and greens and dark blue shadows. As if to underscore the vast power of nature against the frail transience of mankind, Monet’s painting of The Custom Officer’s Cottage at Varengeville (Fogg Art Museum, Harvard) shows the tiny stone hut perched on the windswept headland with a storm-tossed sea below. Man may put his mark on nature, Monet seems to say, but how long will it last?

The obligatory waterlilies made their appearance in Room 3, in which architecture is represented by the delicate arch of Giverny’s Japanese bridge; but I found myself drawn instead to the series of glorious pictures painted in Antibes in 1888. Two views in particular caught my eye, both taken from the same spot: Antibes from la Salis (Private collection) and Antibes, Morning (Philadelphia Museum of Art), in which Monet again uses the classical compositional principles he’d learned from Claude. Yet the conventional framing devices of the foreground trees are coupled with a visionary expressiveness in the macchia, the dabs or spots of paint that Monet uses.

Claude Monet, The Custom Officer’s Cottage at Varengeville, Fogg Art Museum, Harvard

I can’t really choose between these two views: I love the pink-and-gold light on the upper part of the tree in the Philadelphia view, but equally I love the shimmering reflection of the pink city in the water in the painting from a private collection. The verdant colour is even more of a feature in two views of Bordighera from 1884: in Villas at Bordighera (Private collection), we glimpse the tumbling tiers of the city through a riot of exotic gardens, while in the View of Bordighera (Hammer Museum, Los Angeles), Monet’s habitual pastel tones briefly become stronger and darker, in the swirls of greenery on left, the pines on the right, and the dark blue sea beyond, cradled in a cleft of the land.

It’s funny to pass from these almost ecstatic evocations of nature to Monet’s paintings of the city. Room 4 displays a group of pictures from the 1870s, admittedly from an earlier period of his artistic development, but nevertheless strangely unexpressive and literal, as if Monet is trying to translate his style to the dense throng of city life. In the View of the Old Outer Harbour at Le Havre (1874; Philadelphia Museum of Art), it’s almost a shock to see the smoke of steam-ships and the close-packed industry of the busy wharves. Monet doesn’t seem to belong here: it’s as if his heart isn’t in it. He keeps trying – like so many of his peers (I always think especially of Boudin), he goes to the beach at Trouville and paints elegant ladies and gentlemen strolling with their parasols – but it’s only later in the decade that something really seems to click with Monet and city life. Somehow he finds a key to the dynamism of modernity.

Claude Monet, View of Antibes, Philadelphia Museum of Art

In 1877 he was granted permission to paint two views in the Gare St-Lazare (National Gallery and the Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris), where he forms the architecture of iron bridges and station roofs into a matrix to trap and corral the steam from the trains. You can feel some of the thrill of being in Paris at a time of change, especially in the dazzling painting of The rue Montorgueil on the national holiday on 30 June 1878 (Musée d’Orsay, Paris). The whole canvas explodes with the blues, reds and whites of flags. Here is the busy joy of city life bubbling out of the picture. And yet Monet was also sensitive to the quieter world of a simpler life. At the same period that he was painting steam engines and steel bridges, he produced one of his last pictures of Argenteuil, The Ball-Shaped Tree (1876; Private collection), in which the focus isn’t so much on the houses, but again on the architecture of nature: that lollipop-shaped tree replaced in the placid lake.

The really great thing about the exhibition, and the thing that will stick with me, is the way it finished with a prolonged bang, like the best kind of firework display. The first part of the bang comes in the form of five views of the facade of Rouen Cathedral in different lights, all completed in 1894, displayed on one gorgeous wall: one sugary, pink and pale in the setting sun (National Museum of Wales); one articulated with crisp clumps of impasto in white, pale pink and blue, like confections of royal icing (Private collection); one a glimpse before the dawn, tinged with the anticipation of a pink-gold glow (Klassik Stiftung Weimar); and two in cool tones of blue and gold as the shadows of the night dissipate with the sunrise (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; and Beyeler Collection, Basel). It’s one of the most stunning walls I’ve ever seen in a show and, if you turn, you’re greeted by something almost as splendid: three dreamy views of the Houses of Parliament, painted in 1904.

Monet had visited London in 1870, a visit which inspired a rather careful painting of The Houses of Parliament from 1871 (National Gallery), and he returned in 1900 and 1901, which gave him the inspiration for this later series. These are the artist at his most evocative: in one, the shadowy buildings are surrounded by air and water, which share their rippling dawn tones of gold and lilac (Palais des Beaux-Arts, Lille); in another, the real stunner of the three, a sunset turns the sky and river to flame and mist licks at the skirts of the buildings like smoke (Kunsthaus Zurich); and in the last, the towers emerge from a featureless white-lilac mist (Museum of Fine Arts, St Petersburg, Florida).

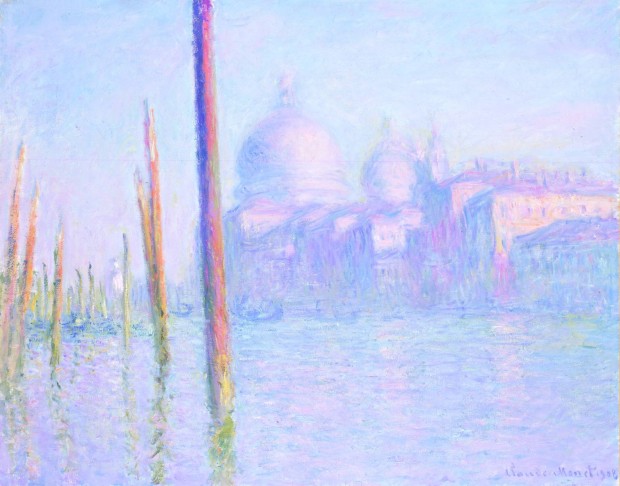

Monet’s sensitivity to light and water is equalled, though not surpassed, by the final selection: some views of Venice from 1908. Inevitably, this city spoke to him deeply: a place in which light and water blend even without the artist’s alchemy. There are two pairs and one trio: the Doge’s Palace is shown twice (Private collection; and Brooklyn Museum); the Salute is seen twice from beneath the Accademia bridge (Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco; and Nahmad Collection, Monaco); and S. Giorgio appears three times in a fleeting, pastelly light (Private collection; Indianapolis Museum of Art; National Museum of Wales). Oddly, for someone who loves Venice as much as I do, I found these pictures less exhilarating than the Rouen or Parliament pictures: instead, they’re deeply calming, in tones of blue, green, pink and lilac. The San Francisco picture made the greatest impact on me, as the buildings seem on the point of melting into their reflections, and the fainter tones of the architecture suggest a dreamy distance.

This show did a great deal to increase my appreciation of Monet – to see him as more than a painter of waterlilies and chocolate-box views, and to appreciate his vigorous technique and dramatic use of light and colour. It was a real treat. Unfortunately it has now closed, but London is blessed with many other fabulous Impressionist pictures, and the National Gallery has just opened a display of some of the very best, on loan from the Courtauld Gallery, which is undergoing a long-term renovation. So there is still much to see, although I’m not sure anything can quite match that wonderful wall of views of Rouen. Sheer magnificence.

Claude Monet, The Grand Canal, Venice, Fine Arts Museum, San Francisco