★★★★★

Although I’m only posting about it now, I finished The King Must Die before embarking on Gates of Fire. My planned project this year is a reread of Mary Renault’s classical history novels, which had such a huge impact on me as an impressionable teenager. Two books stood out particularly strongly in my memory: The King Must Die and Fire From Heaven, and I was delighted to hear that Heloise was also keen to read the former. Our very informal joint reading was punctuated by excited whittering about myths (from me) and fascinating comments about narrative patterns and the question of consent in sacrifice (from her). I’m pleased to report that I’ve infected her with my Renault enthusiasm and in fact she’s already finished the sequel, The Bull From The Sea.

The King Must Die is one of the very few novels in my personal pantheon. It’s so compelling because Renault uses her profound understanding of antiquity and archaeology to offer rational explanations of the Greek myths. She focuses on the tale of Theseus: the young heir to the throne of Athens, chosen as one of seven youths and seven maidens from the city sent as tribute to King Minos of Crete, to be devoured by the fearsome Minotaur in his Labyrinth. In Renault’s version the Labyrinth (literally the House of the Axe) is Minos’ sprawling palace at Knossos, with its warrens of halls, courts and storerooms. The only monsters are all too human; but the bulls, at least, are real.

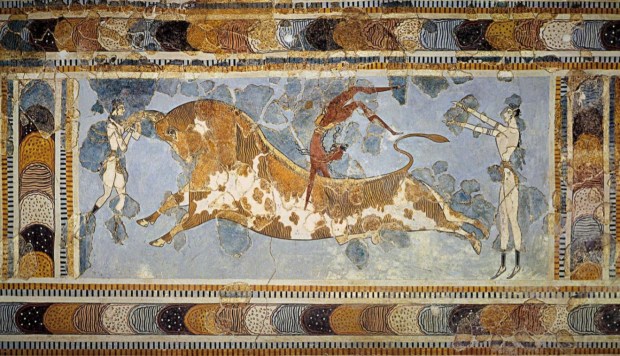

The most gorgeous moments of Renault’s novel take place in the Bull Court, deep within Minos’ palace, where Theseus and his fellow Athenians find themselves facing fate in the form of the graceful, challenging and deadly Bull Dance. And yet Crete is only part of Theseus’ story. From its opening pages, Renault’s novel plunges us into the unfamiliar world of Bronze Age Greece: a patchwork of embryonic kingdoms in which two vitally different religious cultures find themselves on a collision course. The societies she recreates are as compelling and strange as any myth.

Theseus is born in his grandfather’s palace at Troizen in the Peloponnese. As a child he learns that a king’s bond with his people is a double-edged bargain, overseen by the gods. A king is granted the best of all things; but, if his people are struck by plague, drought or natural disaster, it is his duty to offer up his life as a sacrifice, to restore the balance and appease the gods. Such is the way of the Hellenes: the tall, fair raiders from the north who have come into Greece with their patriarchal societies and their Sky Gods. These gods are virile figures who, like Thesus’ favoured Poseidon, make themselves known through the tumult of nature.

But the Hellenes live among the remnants of an earlier culture: the native Shore People (also called Minyans or Earthlings), who are devoted to the Mother, to the cycles of the seasons and the harvest. Among the Shore People, veneration of the Mother expresses itself in matriarchal societies and sovereign priestess-queens. Moreover, their devotion to the annual cycles of the year puts a very different slant on the question of king-sacrifice. In Shore communities, a young man is chosen as the queen’s consort for a year – he is cossetted, cherished and adored – and then, at the turn of the year, he dies. His youthful essence bleeds into the soil to placate the Mother and keep the harvests good. The queen then takes another king, and the cycle begins anew.

This tradition of ritual death is the driving force of the book, and in each of its four sections we witness the (implicitly) willing sacrifice of a king. That question of willingness was one that absorbed both of us, and we wondered how these societies understood consent. Did consent have to be explicitly expressed to be valid? How then to explain animal sacrifice, in which the ritual ‘nod’ of the animal’s head was taken for acceptance? Could you argue that, by accepting the year of celebration and plenty, the Minyan year-kings implicitly accept the associated death that comes at the end of the year? They may not wish to die, but their consent is implicit in their acceptance of the whole package.

That’s where Theseus comes in, of course. A Hellene interloper among the Shore People, he refuses to consider himself bound by their traditions. Using his wits and creativity, he is determined to find a way to break the cycle without (as he sees it) offending the gods. A similar challenge waits for him in Crete, where he is faced with an ancient but decadent civilisation which is ripe for the picking… but how? In both cases, his individual triumph represents in microcosm the triumph of the young, aggressive and energetic Hellene culture over the Shore People. Theseus, like his fellow Hellenes, is simply biding his time. Waiting:

I know how a man looks who foreknows his end. It is in the blood of the Earthlings; they go to it like birds before whose eyes the snake is dancing. But if she dances for the leopard, the leopard jumps first.

His imagination and impetuosity are two of his most appealing features, because there’s no doubt that otherwise he’s not always the most attractive protagonist. Acutely conscious of his short stature, he’s driven by a need to prove himself and his virility; he’s opinionated, arrogant and misogynistic. But there are times when he transcends himself: Crete, ironically, proves to be the making of him. Here he becomes directly responsible for a group of young people – both boys and girls – who will only be able to survive by working together for the good of the whole. And here, in Crete, Theseus discovers that it is no mean thing to be slight of stature. On the contrary, his slim build offers him the most dazzling kind of celebrity: that of the bull-leaper. Graceful, lithe and athletic, these young people – who can still be seen in fading fragments of Minoan frescoes – are the darlings of the court. They’re adored and celebrated; but, as Theseus and his team discover, they are always only one misstep away from death.

This is a treasure-trove for anyone who grew up reading stories of the Greek myths: there’s great satisfaction to be found in following all of Renault’s playful throwaway allusions, whether that’s the death of Adonis, the fate of Medea or the building of Stonehenge (a personal favourite, as a West Country girl). But intelligence and cleverness wouldn’t be enough if Renault wasn’t also a splendid storyteller. Her Theseus might not always be sympathetic, but he feels real: he’s a young man trying to find his place in the world, and Renault’s genius is to show us Theseus’ shortcomings and strengths even though she tells the story through a first-person narration.

And even if these two things weren’t enough, the setting is magical: the splendours of Minoan Crete; the raw beginnings of Athens; the rites and mysteries of the Goddess; all take wing in dazzling flights of the imagination which are all the more thrilling for their plausibility. It’s true that it feels rather more measured, pure and classical than Gates of Fire, for example: if that novel is full of bloodied, ravaged flesh, then Renault’s novel has the restraint of a white marble statue. But both books play, in equally exciting ways, with that fluid borderline between the great deeds of history and myth; and both leave you hungry to find out more about the cultures behind them.

Since Renault’s novel is based on historical fact, there’s plenty more to be explored if you feel so inclined. To kick things off, you might like to visit this very interesting post at Ancient Peoples for more information on bull-leaping in Minoan Crete; while there is a fascinating analysis of the Snake Goddess figurine and Minoan Goddess-worship over at Art History Resources. You might also enjoy Helen’s post on The King Must Die, which she read at the end of last year (she’s probably responsible for inspiring me to reread it). If you know of any lively, readable books on Minoan history – or other historical novels about the period – then as ever please do share them! I’ll be moving on to The Bull from the Sea soon, where Renault tackles the later parts of the Theseus myth; and, quite frankly, I can’t wait.

Bull leapers, shown on a (partially reconstructed) fresco from Knossos

Enjoyed this review, sounds like another I must add to my large TBR pile – which has grown considerably since following your blog!

My favorite of her works…highly recommended. Like a good story-teller, Renault makes the times come alive with her insightful narrative.

I'm not familiar with most of Greek myths, I'm sorry to say, but I like to read about them anyway (or perhaps for that reason).

I read time ago a book about ancient matriarchal civilization that I found gripping, and your review has reminded me of it (it was written by a Spanish author, but I can't remember further details).

Sometimes when I think about stories in which women had the power, it seems as if I'm reading science fiction 😉

Well, I think I have to add this author to my list!

Hello Idle Woman, I’ve just found you after finishing The King Must Die myself and searching reviews of it. As a Classics graduate I really admired the fictionalisation of the historic basis for the Theseus myth. I’d really appreciate it if you could recommend any other fiction that accounts for the evolution of myth, especially Greek. I’m familiar with the Canongate series of retellings which is also good but not a patch on Mary Renault.

Hello Tasha! Thanks so much for your comment. I’ve been racking my brains ever since you posted it and I think I must be having a daft moment because at present I can’t think of anything that treats Greek myth in quite the same way… though of course there must be some!

For a later period, Arthurian legend, Rosemary Sutcliff’s Sword at Sunset is quite similar in feel. And of course there are several books which deal with the dividing lines between historical truth and scriptural authority in the life of Christ. Of those I’ve read, The Testament of Mary by Colm Toibin, The Liars’ Gospel by Naomi Alderman and (partly read, and quite dense) King Jesus by Robert Graves all tackle the issue in an interesting and illuminating way.

But the Greeks? Hmm. Leave me to ponder that. And of course, if anyone else has any brainwaves, I hope they’ll share their thoughts with both of us!