Last week I was sent to Berlin for a few days on business, which meant that I was finally able to knock several major museums off my ‘to do’ list. I’d only been to Berlin once before, as part of a sixth form trip, during which our programme took us to the Reichstag, Checkpoint Charlie and Wansee but signally failed to consider anything pre-1933. In desperation, during a couple of hours’ free time when all the other girls went shopping, I begged my teacher and a hapless friend to come with me to the Gemäldegalerie, and my abiding memory of the entire school trip is standing in front of Caravaggio’s Amor Victorious, uncertain whether to be scandalised or delighted.

Tag: art

Drawn From the Antique (2015)

Artists and the Classical Ideal

(Sir John Soane’s Museum, London, until 26 September 2015)

It’s 1531. A group of men have gathered in a low-ceilinged room in the Belvedere wing of the Vatican. All natural light has been banished. Clustered around a table, they are drawing from a classical statuette, lit only by candlelight to emphasise the curves and shadows of its graceful form. At the back, holding the statuette, is a bearded man in a cap. He is Baccio Bandinelli: sculptor, draughtsman and master of this little group of students. This engraving is the first depiction of artists drawing from classical models, and also the first depiction of a gathering which regarded itself as an art ‘academy’.

Triumph and Disaster: Medals of the Sun King (2015)

(British Museum, until 15 November 2015)

When you think of Louis XIV, chances are that you think of Versailles. The Hall of Mirrors; the fountains and festivals; the gold, glass and glitter of the Ancien Régime. But medals? Maybe not. And yet Louis was responsible for one of the most ambitious and innovative of all medal series, the Histoire medallique. Published in 1702, towards the end of his reign, it aimed to celebrate and promote his victories, both as a military commander and an administrator, and to gloss over his defeats and failures.

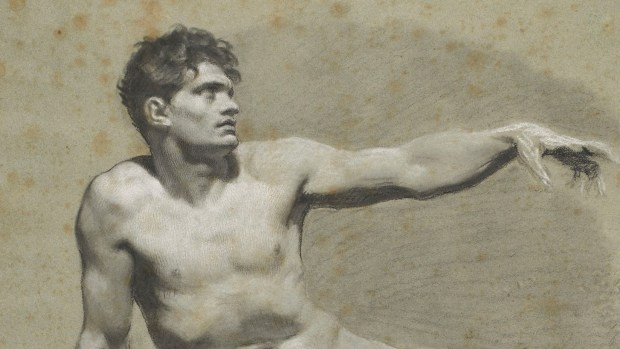

Pierre-Paul Prud’hon: Napoleon’s Draughtsman (2015)

(Dulwich Picture Gallery, until 15 November 2015)

This year there are many exhibitions designed to capitalise on the sudden flourish of enthusiasm for all things Waterloo and Napoleon. This small show at Dulwich shrewdly uses the Bonaparte connection as an excuse for bringing a little-known artist back into the limelight, and bravo to that. I say ‘little-known’ with some caution. Having spent far too long in the art world, I sometimes find it hard to judge how familiar an artist would be to the average passer-by on Oxford Street; but I think I’m safe in assuming that Prud’hon isn’t exactly a household name.

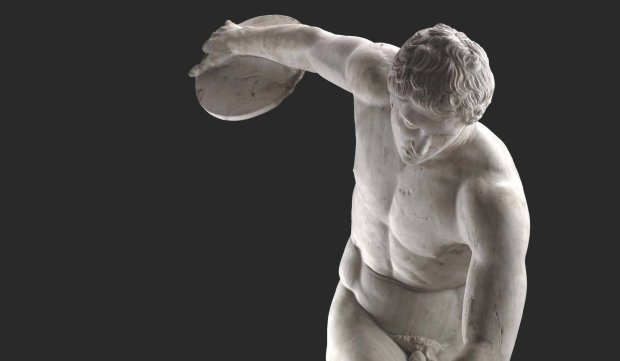

Defining Beauty: The Greek Body (2015)

(British Museum, London, until 5 July 2015)

I’ve been terribly lax at writing about exhibitions recently, and this post is actually far too late because the show has just closed. Nevertheless there were such beautiful things on display that I still wanted to write a little about it; and I hope some of you had the chance to see it. The theme was, very simply, the body in Greek art; but it went beyond the predictable athletic male nude, which for the Greeks, and for so many cultures since, has been the pinnacle of physical perfection. The show also looked at sculptures of the female body, whether divine or mortal; at representations of the body throughout the life cycle; and at sculpture on different scales and in different modes, from heroic to comic.

The Land of the Rising Sun (Tokyo)

In other news, I’ve just got back from my first visit to Japan: a week in Tokyo, on business, which turned out to be one of the most enjoyable and brilliant trips I’ve ever been on. I had the good fortune to travel with some really lovely colleagues from other companies, and our hosts could not have been kinder or more eager to help: Japanese hospitality truly is remarkable and I’ve certainly now been spoiled for life as far as business trips are concerned.

Goya: The Witches and Old Women Album (2015)

(Courtauld Gallery, London, until 25 May 2015)

A man slumps at a table, his head buried in his arms. As he dreams, the dark creatures of his imagination rise out of the shadows behind him: a lynx, which looks up with wide eyes; bats, flocking in the darkness, and owls which mob the sleeping figure with their wings and steal his artist’s tools. This etching, made in 1799, forms part of Goya’s print series Los Caprichos and was originally conceived as an allegorical self-portrait. Its title is The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters. For all of mankind’s pretensions to reason and rationality in this Enlightened age, Goya seems to say, we only have to sleep for our primal nightmares to come crawling out of the woodwork.

Bernini’s Beloved (2012): Sarah McPhee

★★★★½

A Portrait of Costanza Piccolomini

Now here is a love story with a sting in the tail for Valentine’s Day. Written with novelistic verve by Sarah McPhee, a professor at Emory University, it is an example of how art history can be brought to scintillating, pulsing life when done well. McPhee’s point of departure is a striking marble bust of a woman, carved by Bernini in 1637 and traditionally believed to record the features of a woman named Costanza with whom he was passionately in love. Her husband was one of Bernini’s assistants.

A Victorian Obsession: The Pérez Simón Collection (2014-15)

(Leighton House, London, until 29 March 2015)

Tucked away in a quiet street near Holland Park, Leighton House is worth visiting at any time of year, but at the moment it offers more than just the usual dose of elegant Victoriana. The pictures that usually hang on the walls have given way to a selection of paintings from the collection of Juan Antonio Pérez Simón, a Mexican businessman with a particular fondness for British 19th-century painting. Many of the great Victorian pictures are still in private hands, and despite some renewed interest in the field, it’s still a comparatively uncommercial part of the art market. Pérez Simón has been able to build up a simply staggering collection in a relatively short period of time.

Rembrandt: The Late Works (2014-15)

(National Gallery, London, until 18 January 2015)

The National Gallery is currently playing host to another winter blockbuster. Rembrandt might not be quite as unbearably crowded as the Leonardo show was a couple of years back, but I’ve heard that queues are still snaking around the building before opening time. A few days ago I was lucky enough to see the exhibition at a relatively quiet time and it made for a gripping and illuminating experience. There’s a lot to see, which isn’t always a good thing when you have to elbow your way past other visitors, but it’s worth a visit for the sheer quality of the exhibits. The highlights for most people will be the paintings, which are deservedly celebrated, but for me the greatest legacy of the exhibition will be a better appreciation of Rembrandt’s achievements, daring and creativity as a printmaker.